How do English farmers learn and finance agroforestry? New insights from the Agroforestry ELM Test project

Following a well-received evidence review in which the main factors holding back agroforestry in England were identified, the Agroforestry ELM Team, led by the ORC, Woodland Trust, Soil Association, and Abacus Agriculture, have now moved on to detailed interviews of England’s leading agroforestry farmers and analysis of their responses. These interviews have given the clearest picture to date of how English farmers use different sources of information as they proceed from ‘novice’ to ‘expert’ agroforestry farmers, and how agroforestry has been financed by farmers to date.

Nineteen experienced and nine novice (very interested in agroforestry but not yet practicing it) agroforestry farmers have been interviewed by Ian Knight and Stephen Briggs of Abacus Agriculture.

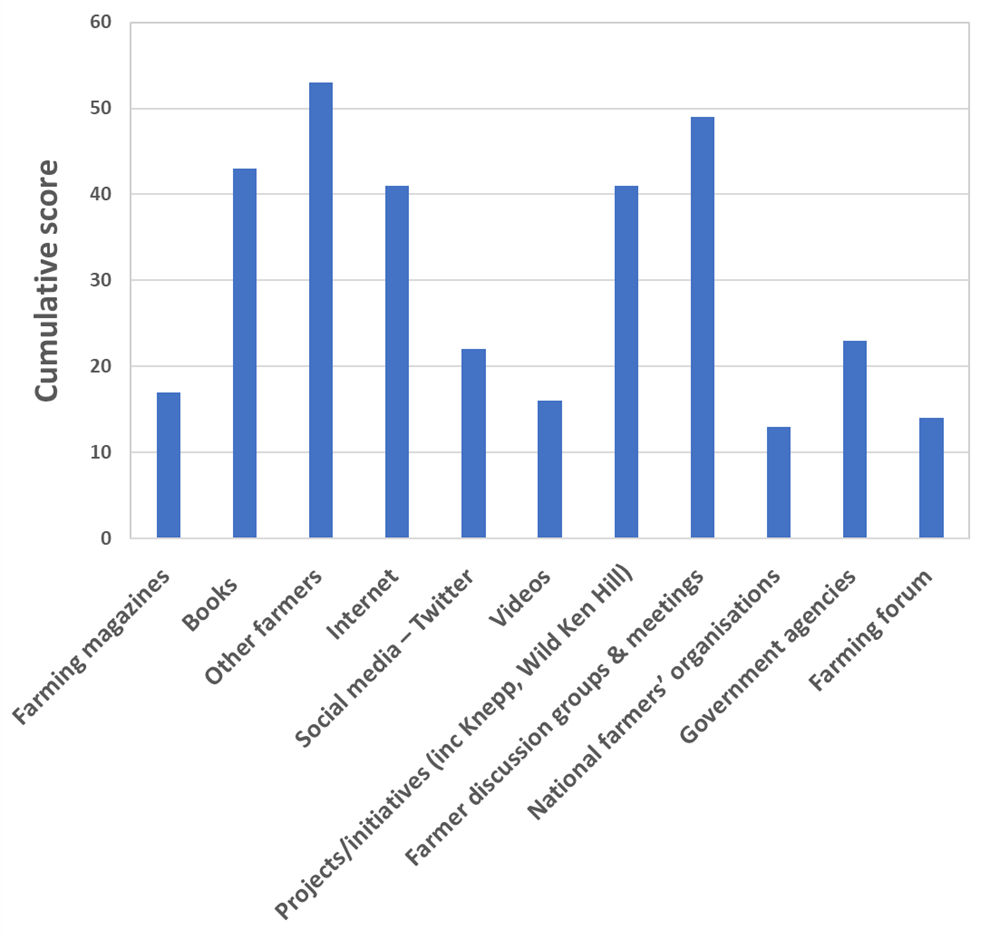

In one part of the interview, farmers were presented with a list of information sources (see the bottom axis of Figure 1) and asked how important they felt each was in their learning of agroforestry. Farmers were also asked to name any information sources missed in the list – most farmers named third sector unpaid sources (Woodland Trust, English Nature etc.) and paid farm advisory services as also being important (this data is not presented here).

Taking Figure 1 and this additional information into account, it is indicated that experienced agroforestry farmers are focused on what could be called ‘serious study’ (books and serious internet resources) and person-to-person interactions (farmer-to-farmer, farmer-to-specialist) in their learning of agroforestry. Experienced farmers appear to be quite discriminating in the information they use. They make little use of online social networks or videos or magazines when learning about agroforestry.

Figure 1: Information sources used by nineteen experienced English agroforestry farmers to learn about agroforestry. Note that farmers also identified unpaid third sector sources and paid advisors as being important. Farmers allocated a score to each source in Figure 1 depending on how important they felt they were, with a high score indicating high importance. These scores were summed up across all participants to get the ‘Cumulative score’ measure on the upright axis

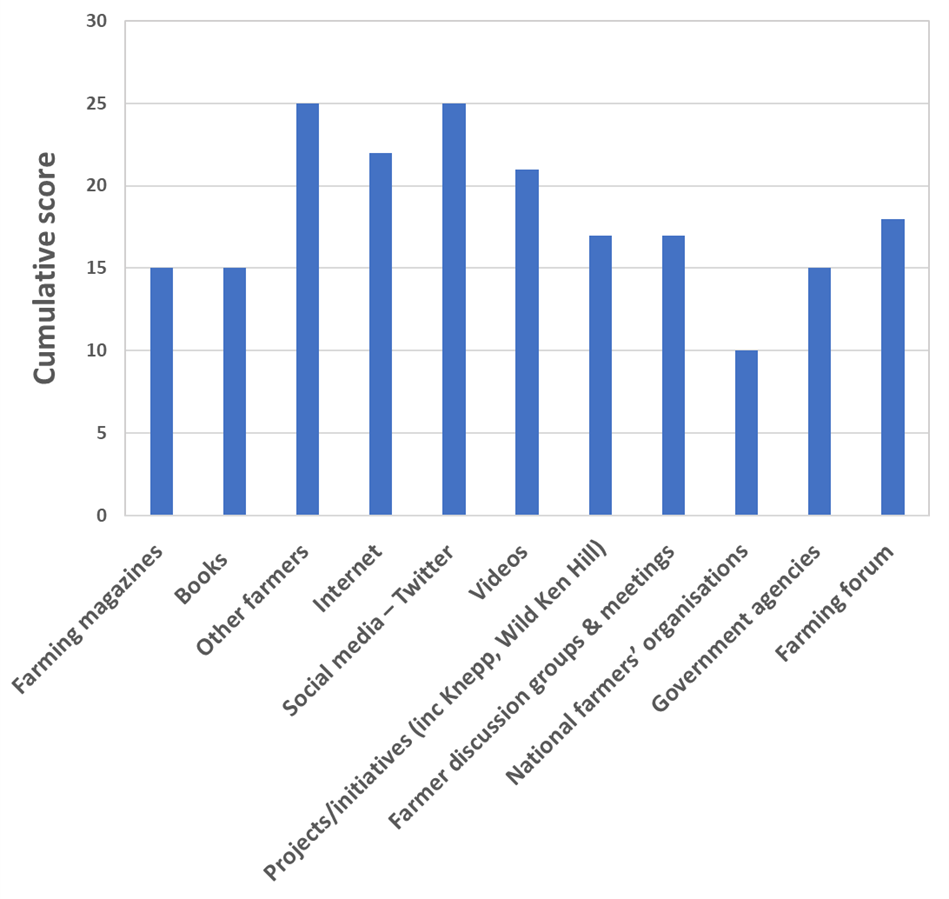

This left us with the nine inexperienced agroforestry farmers. We wondered if they might be different in their use of information, so we analysed them separately. Bearing in mind that they also find unpaid third sector and paid farm advisors important, Figure 2 indicates that they are much less discriminating in the information sources they use. Just about all information sources seem relevant to them, even the relatively superficial ones like magazines, social networks, and videos that experienced farmers make less use of. There are fewer clear ‘standout’ information sources in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Information sources used by nine inexperienced English agroforestry farmers to learn about agroforestry. Note that farmers also identified unpaid third sector sources and paid advisors as being important

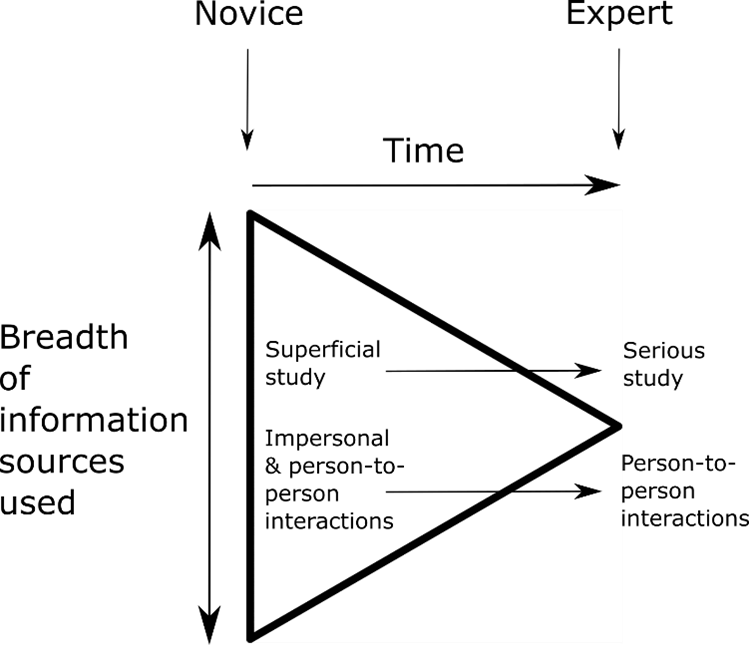

Put this altogether, and the model of agroforestry learning shown in Figure 3 is suggested.

Figure 3: A model of how agroforestry farmers in England have learned agroforestry to date. Refer to the main text for a description

A very broad range of information sources appear able to pique interest in agroforestry in farmers. At this stage of the learning process the study regime of agroforestry farmers is ‘superficial’: farmers use magazines, social media and videos a lot to learn about agroforestry. Learning interactions are both impersonal (electronic) and person-to-person. As expertise in agroforestry develops, farmers narrow the range of information sources they use. Study becomes more classically ‘serious’ involving books and (presumably) technical and long-read internet documents. The way farmers interact during learning also changes. Farmers engage with electronic resources less and switch more exclusively to person-to-person interactions.

What does all this mean for agroforestry in England? How can this take agroforestry forward? The first implication is that if farmers want to learn more about agroforestry, magazines, social media, videos, and other relatively superficial internet-based resources will only take them so far. Development of expertise requires intense study and person-to-person interaction with people who are already agroforestry experts. Farmers wishing to learn about agroforestry should contact known experts and ask them when their next farm visit is, or get themselves along to a farmer discussion group and find an expert there. They should also be asking agroforestry experts which books and detailed technical documents they have used when they meet them.

The second implication is in relation to agroforestry knowledge exchange. Knowledge exchange professionals who are interacting with farmers on social media should not be directing farmers who have found online agroforestry videos or blogs interesting to more of the same. They should be encouraging farmers to make the transition to expert by directing them to expert individuals or discussion groups where farmers can have person-to-person interactions, and they should be directing farmers to deeper sources of personal study.

Lastly, assuming Defra plan to facilitate the process of agroforestry learning in ELM, the findings seem to dash any possibility that there is a single overriding information source that is most important in the learning of agroforestry. Sources that farmers use to learn agroforestry are clearly broad, even when they transition to expert. That said, there are some information sources that are important at all stages of the learning process, most notably farmer-to-farmer interactions. This would seem an obvious area of investment for Defra – to facilitate learning of agroforestry. One idea that has proved popular in Agroforestry ELM Test farmer workshops to date is that expert agroforestry farmers could be paid to conduct farm tours and other interactions they take part in to help other farmers learn agroforestry.

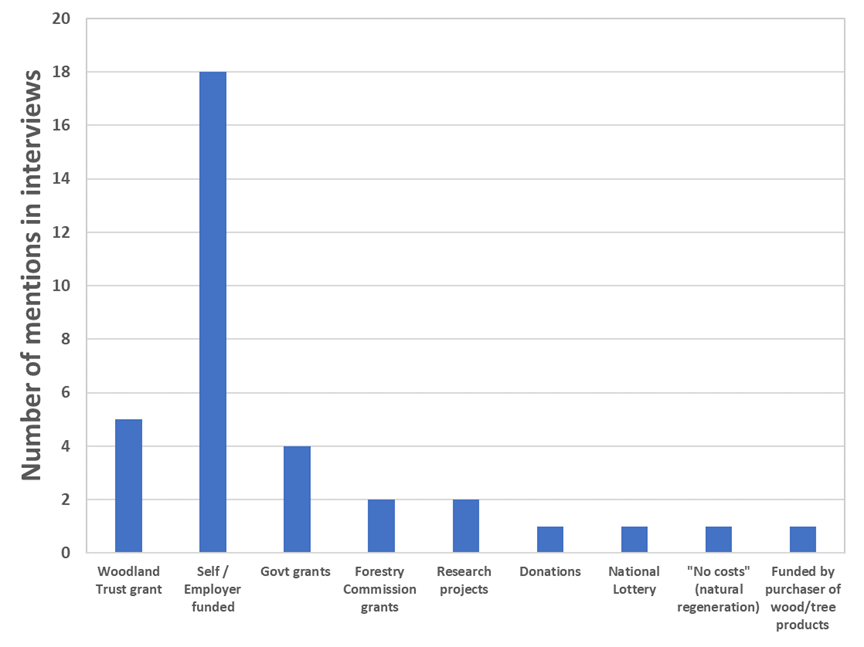

Our analysis of the funding of agroforestry in England to date was much more straightforward. Here we didn’t present farmers with options during interviews; we simply listened to what they said and created response categories and summed up ‘mentions’ in each category. The results are striking and clear (Figure 4). Overwhelmingly agroforestry in England to date has been paid for out of the farmers’ own pocket. Funding schemes such as the Woodland Trust’s “Trees for your Farm” and state schemes like Countryside Stewardship pale in comparison to self-financing.

Figure 4: Financing of agroforestry in England to date. Mentions of different funding sources were summed up to create the graph. (Only the nineteen experienced agroforestry farmers were included in analysis)

This situation does not, of course, seem entirely fair as many agroforestry farmers plant trees with genuine intentions to improve the natural environment for themselves and others. It probably explains why uptake of agroforestry in England is low, and the financing of agroforestry is the second major area that farmer workshops within the Agroforestry ELM Test project are addressing. It is a little too early to feedback on this very complex area as workshops are still ongoing (sign up for remaining workshops here), but workshops will be completed by Christmas 2021 and we hope to able to provide some insights on how farmers want to be compensated for undertaking agroforestry within the ELM system early in the new year.

Header image was taken at Paul & Nic Renison‘s farm ‘Cannerheugh’ in Renwick, Cumbria, by Janie Caldbeck