Are we mining the soil?

Farmers and researchers explore the potential for improving nitrogen (N) efficiency in organic rotations.

Organic principles and standards emphasise the importance of practices that can encourage the long-term health and fertility of agricultural soils. Effective crop rotation, cultivation regimes and organic fertiliser application are therefore important elements of the organic approach. Whilst such practices can undoubtedly increase the soil’s health, their true impact is still uncertain, particularly with regard to soil nutrient and organic matter contents.

Introducing NDICEA

As part of the OK-Net Arable project, a group of organic farmers wanted to improve their understanding in this complex area. This was done by using a computer-based nutrient budgeting model called NDICEA.1 A researcher from the Organic Research Centre visited each farm for a couple of hours to assess individual field rotations using the model. The farmers provided data on climate, soil properties and management practices (e.g. seed rates, fertiliser application, cultivation regimes etc.) for one of their fields. Using this data, NDICEA is able to work out where nutrient surpluses and deficiencies occur over the seasons and rotation cycle. This information is used to provide information on environmental impacts like N leaching and identify if rotations are balanced, helping to build soil fertility or mining nutrients and organic matter.

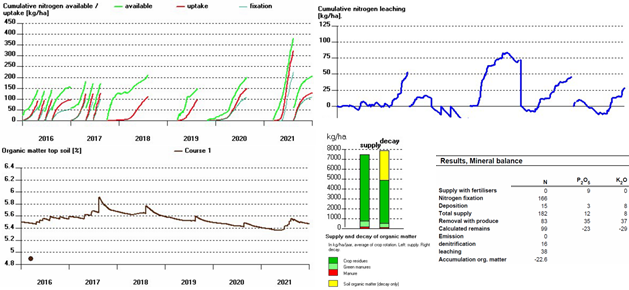

NDICEA outputs include graphs of nitrogen uptake vs. availability (A), leaching (B), organic matter in the top soil (C), supply and decay of organic matter (D) and a table showing mineral balances (E)

Farmer experiences

Seven organic farms took the opportunity to look at one or more of their fields. They entered their crop rotation and management practices to see where, if anywhere, problems arose. The results caused some surprise for both farmers and researchers…

In all cases except one, organic matter was found to decline over the course of the rotation, even where leys with a high clover content formed a substantial part of the cropping sequence. Declines in organic matter were even seen on a farm with six years of grass/clover ley. Similarly, only one farm maintained a positive balance of phosphate and potassium. The only way it achieved this was through annual applications of either compost (35 tonnes per hectare (t ha-1) or chicken manure (10-17 t ha-1) for six (out of eight) years of the rotation.

An additional discovery was that a lot of the nutrients added to the field through fertilisers (including compost or manure) or grass/clover leys were being lost through leaching or harvest. Even with grazing and no cutting, leys high in clover only retained the soil N and did not increase it, whilst gains in organic matter across the ley were only seen with reduced tillage AND when the last cut of forage was left on the field/ploughed in. Meanwhile, breaking the ley in the autumn led to most of the nutrients added being lost before the growing season of the next crop began, due to leaching and denitrification losses over winter.

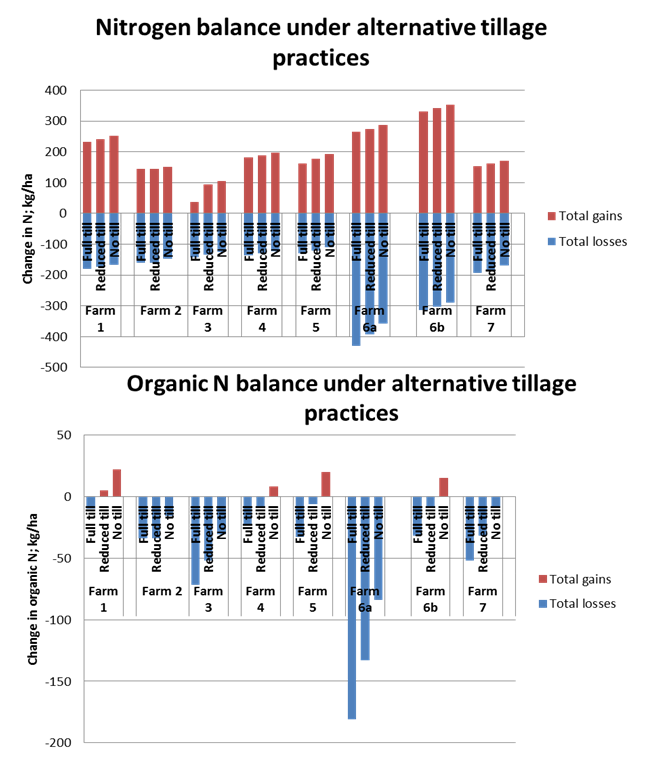

The model also allowed the farmers to adjust their rotations to see what might happen if they changed their rotation or management practices. The seven farms experimented in a number of ways, e.g. exploring the effect of changing fertilisers, cover crops, ley duration and tillage practices. This exercise illustrated just how difficult it was to maintain positive nutrient and organic matter balances over their crop rotations.

Outcomes revealed

- The biggest improvements were seen by changing tillage practices. The difference between conventional and reduced till, and reduced till and no till, were substantial for all the modelled rotations. In many cases this was enough to give positive nutrient balances. In some cases it built organic matter too. This is shown in the graphs above.

- Leaving the straw behind has very little effect on nutrient balances. It does, however, increase organic matter.

- Breaking the ley in the spring doesn’t improve overall nutrient or organic matter balances. What it does do is make the nutrients from the ley available for the following crop, by reducing the amount of nutrients lost over the winter months. This is true even when the crop following the ley is planted in the autumn.

- Using digestate from anaerobic digestion could present an alternative to rock phosphate. In addition to supplying phosphate, digestate can add nitrates, potassium and organic matter to the soil.

- Increasing the yield of a grass/clover ley can lead to substantial benefits, improving organic matter balances and soil nutrient retention.

It must be remembered that no model is 100% accurate and that the outputs given by NDICEA are indications rather than definite outcomes. Despite this, the seven farms all reported just how useful the experience had been. Overall, the work has revealed some real problems to be addressed within organic arable farming. As farmer John Pawsey (pictured above) said: “No matter which way you look at it we are all mining the soil, unless we are bringing in nutrients to balance exports of meat, straw, forage and grain.” Certainly a challenge for the future.

The NDICEA tool is available to download for free from here. Detailed instructions on how to use the tool are available from the same link.

1 Nitrogen Dynamics In Crop rotations in Ecological Agriculture, developed at Wageningen University and the Louis Bolk Institute

Header image photo credit: Katie Bliss